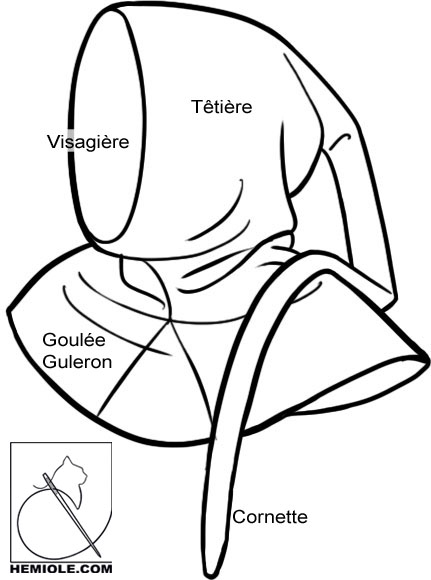

Many pathological states involve changes in this balance, resulting in loss of regulatory control or loss of resilience during stress. Together these findings show that the ubiquitin-activated interaction trap (UBAIT) fusion system can efficiently isolate the complex interactome of HSP chaperone family proteins under normal and stress conditions.Įvery cell has a finely tuned balance of protein expression, folding, complex formation, localization, and degradation that is specific to its growth state and environmental cues. In addition, expression of an amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS)-associated superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) mutant protein induces changes in HSP70 and HSC70 client association and aggregation toward polypeptides with predicted disorder, indicating that there are global effects from a single misfolded protein that extend to many clients within chaperone networks. Both proteins show a preference for association with newly synthesized polypeptides, but each responds differently to changes in the stoichiometry of proteins in obligate multi-subunit complexes. Here, we demonstrate quantitative identification of HSP70 and 71 kDa heat shock cognate (HSC70) clients using a ubiquitin-mediated proximity tagging strategy and show that, despite their high degree of similarity, these enzymes have largely nonoverlapping specificities. when used metaphorically means that the experienced married woman shelters the youthful débutante as a hood shelters the face”.The 70 kDa heat shock protein (HSP70) family of chaperones are the front line of protection from stress-induced misfolding and aggregation of polypeptides in most organisms and are responsible for promoting the stability, folding, and degradation of clients to maintain cellular protein homeostasis. About a century later the word began to be used figuratively for a married or elderly woman protecting a young woman - a chaperone, as we now spell it. The hoods went out of fashion in the fifteenth century and liripipe became a semi-fossil word, most commonly used today by historians of fashion and the occasional academic institution.īy the seventeenth century, the chaperon had become an item of female costume exclusively. As well as longer, it also grew more ornamental as time passed. Over time, liripipes became steadily longer, sometimes down to the ankles this was hardly practical, so the liripipe was often wound around the head to keep it out of the way. Later on, liripipes became part of everyday wear on a hood called a chaperon, a word that is closely related to the modern French chapeau. Hoods like these were at first worn by academics as part of their formal dress indeed a few universities still use the word liripipe for their graduates’ ceremonial sashes. What we do know is that the English word (on occasion appearing as liripoop, for reasons that are entirely obscure) was used for a dangling extension to the point of a medieval hood. This suggests strongly that nobody has the slightest idea what it really meant.

Nobody seems to know much about the origin of this word, except that it comes from medieval Latin liripipium, variously explained down the centuries as the tippet of a hood, a cord, a shoe-lace and the inner sole-leather of shoes.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)